This module will discuss the fundamental data concepts of Hoon and how programs handle control flow.

The study of Hoon can be divided into two parts: syntax and semantics.

The syntax of a programming language is the set of rules that determine what counts as admissible code in that language. It determines which characters may be used in the source, and also how these characters may be assembled to constitute a program. Attempting to run a program that doesn’t follow these rules will result in a syntax error.

The semantics of a programming language concerns the meaning of the various parts of that language’s code.

In this lesson we will give a general overview of Hoon’s syntax. By the end of it, you should be familiar with all the basic elements of Hoon code.

Hoon Elements

An expression is a combination of characters that a language interprets and evaluates to produce a value. All Hoon programs are built of expressions, rather like mathematical equations. Hoon expressions are built along a backbone of runes, which are two-character symbols that act like keywords in other programming languages to define the syntax, or grammar, of the expression.

Runes are the building blocks of all Hoon code, represented as a pair of non-alphanumeric ASCII characters. Runes form expressions; runes are used how keywords are used in other languages. In other words, all computations in Hoon ultimately require runes. Runes and other Hoon expressions are all separated from one another by either two spaces or a line break.

All runes take a fixed number of “children” or “daughters”. Children can themselves be runes with children, and Hoon programs work by chaining through these until a value—not another rune—is arrived at. For this reason, we very rarely need to close expressions. Keep this scheme in mind when examining Hoon code.

Hoon expressions can be either basic or complex. Basic expressions of Hoon are fundamental, meaning that they can’t be broken down into smaller expressions. Complex expressions are made up of smaller expressions (which are called subexpressions).

The Urbit operating system hews to a conceptual model wherein each expression takes place in a certain context (the subject). While sharing a lot of practicality with other programming paradigms and platforms, Urbit's model is mathematically well-defined and unambiguously specified. Every expression of Hoon is evaluated relative to its subject, a piece of data that represents the environment, or the context, of an expression.

At its root, Urbit is completely specified by Nock, sort of a machine language for the Urbit virtual machine layer and event log. However, Nock code is basically unreadable (and unwriteable) for a human. One worked example yields, for decrementing a value by one, the Nock formula:

[8 [1 0] 8 [1 6 [5 [0 7] 4 0 6] [0 6] 9 2 [0 2] [4 0 6] 0 7] 9 2 0 1]

This is like reading binary machine code: we mortals need a clearer vernacular.

Hoon serves as Urbit's practical programming language. Everything in Urbit OS is written in Hoon, and many of the ancillary tools as well.

Any operation in Urbit ultimately results in a value. Much like machine language designates any value as a command, an address, or a number, a Hoon value is interpreted per the Nock rules and results in a basic data value at the end. So what are our data values in Hoon, and how do they relate to each other?

Nouns

Think about a child persistently asking you what a thing is made of. At first, you may respond, “plastic”, or “metal”. Eventually, the child may wear you down to a more fundamental level: atoms and molecules (bonded atoms).

In a very similar sense, everything in a Hoon program is an atom or a bond. Metaphorically, a Hoon program is a complex molecule, a digital chemistry that describes one mathematical representation of data.

The most general data category in Hoon is a noun. This is just about as broad as saying “thing”, so let's be more specific:

A noun is an atom or a cell.

Progress? We can say, in plain English, that

- An atom is a non-negative integer number (0 to +∞), e.g.

42. - A cell is a pair of two nouns, written in square brackets, e.g.

[0 1].

Everything in Hoon (and Nock, and Urbit) is a noun. The Urbit OS itself is a noun. So given any noun, the Urbit VM simply applies the Nock rules to change the noun in well-defined mechanical ways.

Atoms

If an atom is a non-negative number, how do we represent anything else? Hoon provides each atom an aura , a tag which lets you treat a number as text, time, date, Urbit address, IP address, and much more.

An aura always begins with @ pat, which denotes an atom (as opposed to a cell, ^ ket, or the general noun, * tar). The next letter or letters tells you what kind of representation you want the value to have.

For instance, to change the representation of a regular decimal number like 32 to a binary representation (i.e. for 2⁵), use @ub:

> `@ub`320b10.0000

(The tic marks are a shorthand which we'll explain later.)

Aura values are all designed to be URL-safe↗, so the European-style thousands separator . dot is used instead of the English , com. 1.000 is one thousand, not 1.0 one with a fractional part of zero.

While there are dozens of auras for specialized applications, here are the most important ones for you to know:

| Aura | Meaning | Example | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

@ | Empty aura | 100 | (displays as @ud) |

@da | Date (absolute) | ~2022.2.8..16.48.20..b53a | Epoch calculated from 292 billion B.C. |

@p | Ship name | ~zod | |

@rs | Number with fractional part | .3.1415 | Note the preceding . dot. |

@t | Text (“cord”) | 'hello' | One of Urbit's several text types; only UTF-8 values are valid. |

@ub | Binary value | 0b1100.0101 | |

@ud | Decimal value | 100.000 | Note that German-style thousands separator is used, . dot. |

@ux | Hexadecimal value | 0x1f.3c4b |

Hearkening back to our discussion of interchangeable representations in Lesson -1, you can see that these are all different-but-equivalent ways of representing the same underlying data values.

There's a special value that recurs in many contexts in Hoon: ~ sig is the null or zero value.

The ^- kethep rune is useful for ensuring that everything in the second child matches the type (aura) of the first, e.g.

^- @ux 0x1ab4

We will use ^- kethep extensively to enforce type constraints, a very useful tool in Hoon code.

Exercise: Aura Conversions

Convert between some of the given auras at the Dojo prompt, e.g.:

100to@p0b1100.0101to@p0b1100.0101to@ux0b1100.0101to@ud~to any other aura

Cells

A cell is a pair of nouns. Cells are traditionally written using square brackets: []. For now, just recall the square brackets and that cells are always pairs of values.

[1 2][@p @t][[1 2] [3 4]]

This is actually a shorthand for a rune as well, :- colhep

:- 1 2

produces a cell [1 2]. You can chain these together:

:- 1 :- 2 3

to produce [1 [2 3]] or [1 2 3].

We deal with cells in more detail below.

Hoon as Noun

We mentioned earlier that everything in Urbit is a noun, including the program itself. This is true, but getting from the rune expression in Hoon to the numeric expression requires a few more tools than we currently are prepared to introduce.

For now, you can preview the structure of the Urbit OS as a noun by typing . dot at the Dojo prompt. This displays a summary of the structure of the operating function itself as a noun.

Verbs (Runes)

The backbone of any Hoon expression is a scaffolding of runes , which are essentially mathematical relationships between daughter components. If nouns are nouns, then runes are verbs: they describe how nouns relate. Runes provide the structural and logical relationship between noun values.

A rune is just a pair of ASCII characters (a digraph). We usually pronounce runes by combining their characters’ names, e.g.: "kethep" for ^-, "bartis" for |=, and "barcen" for |%.

For instance, when we called a function earlier (in Hoon parlance, we slammed a gate), we needed to provide the %- cenhep rune with two bits of information, a function name and the values to associate with it:

%-add[1 2]

The operation you just completed is straightforward enough: 1 + 2, in many languages, or (+ 1 2) in a Lisp dialect↗ like Clojure↗. Literally, we can interpret %- add [1 2] as “evaluate the add core on the input values [1 2]”.

The ++add function expects precisely two values (or arguments), which are provided by %- in the neighboring child expression as a cell. There's really no limit to the complexity of Hoon expressions: they can track deep and wide. They also don't care much about layout, which leaves you a lot of latitude. The only hard-and-fast rule is that there are single spaces (aces) and everything else (gaps).

%-add[%-(add [1 2]) 3]

(Notice that inside of the [] cell notation we are using a slightly different form of the %- rune call. In general, there are several ways to use many runes, and we will introduce these gradually. We'll see more expressive ways to write Hoon code after you're comfortable using runes.)

For instance, here are some of the standard library functions which have a similar architecture in common:

++add(addition)++sub(subtraction, positive results only—what happens if you subtract past zero?)++mul(multiplication)++div(integer division, no remainder)++pow(power or exponentiation)++mod(modulus, remainder after integer division)++dvr(integer division with remainder)++max(maximum of two numbers)++min(minimum of two numbers)

Rune Expressions

Any Hoon program is architected around runes. If you have used another programming language, you can see these as analogous to keywords, although they also make explicit what most language syntax parsers leave implicit. Hoon aims at a parsimony of representation while leaving latitude for aesthetics. In other words, Hoon strives to give you a unique characteristic way of writing a correct expression, but it leaves you flexibility in how you lay out the components to maximize readability.

We are only going to introduce a handful of runes in this lesson, but by the time we're done with Hoon School, you'll know the twenty-five or so runes that yield 80% of the capability.

Exercise: Identifying Unknown Runes

Here is a lightly-edited snippet of Hoon code. Anything written after a :: colcol is a comment and is ignored by the computer. (Comments are useful for human-language explanations.)

%- send:: forwards compatibility with next-dill?@ p.kyz [%txt p.kyz ~]?: ?= %hit -.p.kyz[%txt ~]?. ?= %mod -.p.kyzp.kyz=/ =@c?@ key.p.kyz key.p.kyz?: ?= ?(%bac %del %ret) -.key.p.kyz`@`-.key.p.kyz~-?: ?= %met mod.p.kyz [%met c] [%ctl c]

- Mark each rune.

- For each rune, find its corresponding children. (You don't need to know what a rune does to identify how things slot together.)

- Consider these questions:

- Is every pair of punctuation marks a rune?

- How can you tell a rune from other kinds of marks?

One clue: every rune in Hoon (except for one, not in the above code) has at least one child.

Exercise: Inferring Rune Behavior

Here is a snippet of Hoon code:

^- list:~ [hen %slip %e %init ~][hen %slip %d %init ~][hen %slip %g %init ~][hen %slip %c %init ~][hen %slip %a %init ~]==

Without looking it up first, what does the == hephep and -- tistis do for the :~ colsig rune? Hint: some runes can take any number of arguments.

Most runes are used at the beginning of a complex expression, but there are exceptions. For example, the runes -- hephep and == tistis are used at the end of certain expressions.

Aside: Writing Incorrect Code

At the Dojo, you can attempt to operate using the wrong values; for instance, ++add doesn't know how to add three numbers at the same time.

> %- add [1 2 3]-need.@-have.[@ud @ud]nest-faildojo: hoon expression failed

So this statement above is syntactically correct (for the %- rune) but in practice fails because the expected input arguments don't match. Any time you see a need/have pair, this is what it means.

Rune Families

Runes are classified by family (with the exceptions of -- hephep and == tistis). The first of the two symbols indicates the family—e.g., the ^- kethep rune is in the ^ ket family of runes, and the |= bartis and |% barcen runes are in the | bar family. The runes of particular family usually have related meanings. Two simple examples: the runes in the | bar family are all used to create cores, and the runes in the : col family are all used to create cells.

Rune expressions are usually complex, which means they usually have one or more subexpressions. The appropriate syntax varies from rune to rune; after all, they’re used for different purposes. To see the syntax rules for a particular rune, consult the rune reference. Nevertheless, there are some general principles that hold of all rune expressions.

Runes generally have a fixed number of expected children, and thus do not need to be closed. In other languages you’ll see an abundance of terminators, such as opening and closing parentheses, and this way of doing this is largely absent from Urbit. That’s because all runes take a fixed number of children. Children of runes can themselves be runes (with more children), and Hoon programs work by chaining through these series of children until a value—not another rune—is arrived at. This makes Hoon code nice and neat to look at.

Tall and Wide Forms

We call rune expressions separated by gaps tall form and those using parentheses wide form. Tall form is usually used for multi-line expressions, and wide form is used for one-line expressions. Most runes can be used in either tall or wide form. Tall form expressions may contain wide form subexpressions, but wide form expressions may not contain tall form.

The spacing rules differ in the two forms. In tall form, each rune and subexpression must be separated from the others by a gap: two or more spaces, or a line break. In wide form the rune is immediately followed by parentheses ( ), and the various subexpressions inside the parentheses must be separated from the others by an ace: a single space.

Seeing an example will help you understand the difference. The :- colhep rune is used to produce a cell. Accordingly, it is followed by two subexpressions: the first defines the head of the cell, and the second defines the tail. Here are three different ways to write a :- colhep expression in tall form:

> :- 11 22[11 22]> :- 1122[11 22]> :-1122[11 22]

All of these expressions do the same thing. The first example shows that, if you want to, you can write tall form code on a single line. Notice that there are two spaces between the :- colhep rune and 11, and also between 11 and 22. This is the minimum spacing necessary between the various parts of a tall form expression—any fewer will result in a syntax error.

Usually one or more line breaks are used to break up a tall form expression. This is especially useful when the subexpressions are themselves long stretches of code. The same :- colhep expression in wide form is:

> :-(11 22)[11 22]

This is the preferred way to write an expression on a single line. The rune itself is followed by a set of parentheses, and the subexpressions inside are separated by a single space. Any more spacing than that results in a syntax error.

Nearly all rune expressions can be written in either form, but there are exceptions. |% barcen and |_ barcab barcab expressions, for example, can only be written in tall form. (Those are a bit too complicated to fit comfortably on one line anyway.)

Nesting Runes

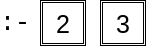

Since runes take a fixed number of children, one can visualize how Hoon expressions are built by thinking of each rune being followed by a series of boxes to be filled—one for each of its children. Let us illustrate this with the :- colhep rune.

Here we have drawn the :- colhep rune followed by a box for each of its two children. We can fill these boxes with either a value or an additional rune. The following figure corresponds to the Hoon expression :- 2 3.

This, of course, evaluates to the cell [2 3].

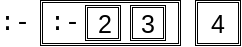

The next figure corresponds to the Hoon expression :- :- 2 3 4.

This evaluates to [[2 3] 4], and we can think of the second :- colhep as being “nested” inside of the first :- colhep.

What Hoon expression does the following figure correspond to, and what does it evaluate to?

This represents the Hoon expression :- 2 :- 3 4, and evaluates to [2 [3 4]]. (If you input this into dojo it will print as [2 3 4], which we'll consider later.)

Thinking in terms of such “LEGO brick” diagrams can be a helpful learning and debugging tactic.

Preserving Values with Faces

A Hoon expression is evaluated against a particular subject, which includes Hoon definitions and the standard library, as well as any user-specified values which have been made available. Unlike many procedural programming languages, a Hoon expression only knows what it has been told explicitly. This means that as soon as we calculate a value, it returns and falls back into the ether.

%- sub [5 1]

Right now, we don't have a way of preserving values for subsequent use in a more complicated Hoon expression.

We are going to store the value as a variable, or in Hoon, “pin a face to the subject”. Hoon faces aren't exactly like variables in other programming languages, but for now we can treat them that way, with the caveat that they are only accessible to daughter or sister expressions.

When we used ++add or ++sub previously, we wanted an immediate answer. There's not much more to say than 5 + 1. In contrast, pinning a face accepts three daughter expressions: a name (or face), a value, and the rest of the expression.

=/ perfect-number 28%- add [perfect-number 10]

This yields 38, but if you attempt to refer to perfect-number again on the next line, the Dojo fails to locate the value.

> =/ perfect-number 28%- add [perfect-number 10]38> perfect-number-find.perfect-numberdojo: hoon expression failed

This syntax is a little bit strange in the Dojo because subsequent expressions, although it works quite well in long-form code. The Dojo offers a workaround to retain named values:

> =perfect-number 28> %- add [perfect-number 10]38> perfect-number28

The difference is that the Dojo “pin” is permanent until deleted:

=perfect-number

rather than only effective for the daughter expressions of a =/ tisfas rune. (We also won't be able to use this Dojo-style pin in a regular Hoon program.)

Exercise: A Large Power of Two

Create two numbers named two and twenty, with appropriate values, using the =/ tisfas rune.

Then use these values to calculate 2²⁰ with ++pow and %- cenhep.

Containers & Basic Data Structures

Atoms are well and fine for relatively simple data, but we already know about cells as pairs of nouns. How else can we think of collections of data?

Cells

A cell is formally a pair of two objects, but as long as the second (right-hand) object is a cell, these can be written stacked together:

> [1 [2 3]][1 2 3]> [1 [2 [3 4]]][1 2 3 4]

This convention keeps the notation from getting too cluttered. For now, let's call this a “running cell” because it consists of several cells run together.

Since almost all cells branch rightwards, the pretty-printer (the printing routine that the Dojo uses) prefers to omit [] brackets marking the rightmost cells in a running cell. These read to the right—that is, [1 2 3] is the same as [1 [2 3]].

Exercise: Comparing Cells

Enter the following cells:

[1 2 3][1 [2 3]][[1 2] 3][[1 2 3]][1 [2 [3]]][[1 2] [3 4]][[[1 2] [3 4]] [[5 6] [7 8]]]

Note which are the same as each other, and which are not. We'll look at the deeper structure of cells later when we consider trees.

Lists

A running cell which terminates in a ~ sig (null) atom is a list.

What is

~'s value? Try casting it to another aura.~is the null value, and here acts as a list terminator.

Lists are ubiquitous in Hoon, and many specialized tools exist to work with them. (For instance, to apply a gate to each value in a list, or to sum up the values in a list, etc.) We'll see more of them in a future lesson.

Exercise: Making a List from a Null-Terminated Cell

You can apply an aura to explicitly designate a null-terminated running cell as a list containing particular types of data. Sometimes you have to clear the aura using a more general aura (like @) before the conversion can work.

> `(list @ud)`[1 2 3 ~]~[1 2 3]> `(list @ux)`[1 2 3 ~]mint-nice-need.?(%~ [i=@ux t=it(@ux)])-have.[@ud @ud @ud %~]nest-faildojo: hoon expression failed> `(list @)`[1 2 3 ~]~[1 2 3]> `(list @ux)``(list @)`[1 2 3 ~]~[0x1 0x2 0x3]

Text

There are two ways to represent text in Urbit: cords (@t aura atoms) and tapes (lists of individual characters). Both of these are commonly called “strings”↗.

Why represent text? What does that mean? We have to have a way of distinguishing words that mean something to Hoon (like list) from words that mean something to a human or a process (like 'hello world').

Right now, all you need to know is that there are (at least) two valid ways to write text:

'with single quotes'as a cord."with double quotes"as text.

We will use these incidentally for now and explain their characteristics in a later lesson. Cords and text both use UTF-8↗ representation, but all actual code is ASCII↗.

> "You can put ½ in quotes, but not elsewhere!""You can put ½ in quotes, but not elsewhere!"> 'You can put ½ in single quotes, too.''You can put ½ in single quotes, too.'> "Some UTF-8: ἄλφα""Some UTF-8: ἄλφα"

Exercise: ASCII Values in Text

A cord (@t) represents text as a sequence of characters. If you know the ASCII↗ value for a particular character, you can identify how the text is structured as a number. (This is most easily done using the hexadecimal @ux representation due to bit alignment.)

If you produce a text string as a cord, you can see the internal structure easily in Hoon:

> `@ux`'Mars'0x7372.614d

that is, the character codes 0x73 = 's', 0x72 = 'r', 0x61 = 'a', and 0x4d = 'M'. Thus a cord has its first letter as the smallest (least significant, in computer-science parlance) byte.

Making a Decision

The final rune we introduce in this lesson will allow us to select between two different Hoon expressions, like picking a fork in a road. Any computational process requires the ability to distinguish options. For this, we first require a basis for discrimination: truthness.

Essentially, we have to be able to decide whether or not some value or expression evaluates as %.y true (in which case we will do one thing) or %.n false (in which case we do another). At this point, our basic expressions are always mathematical; later on we will check for existence, for equality of two values, etc.

++gth(greater than>)++lth(less than<)++gte(greater than or equal to≥)++lte(less than or equal to≤)

If we supply these with a pair of numbers to a %- cenhep call, we can see if the expression is considered %.y true or %.n false.

> %- gth [5 6]%.n> %- lth [7 6]%.n> %- gte [7 6]%.y> %- lte [7 7]%.y

Given a test expression like those above, we can use the ?: wutcol rune to decide between the two possible alternatives. ?: wutcol accepts three children: a true/false statement, an expression for the %.y true case, and an expression for the %.n false case.

Piecewise mathematical functions↗ require precisely this functionality. For instance, the Heaviside function is a piecewise mathematical function which is equal to zero for inputs less than zero and one for inputs greater than or equal to zero.

However, we don't yet know how to represent a negative value! All of the decimal values we have used thus far are unsigned (non-negative) values, @ud. For now, the easiest solution is to just translate the Heaviside function so it activates at a different value:

Thus equipped, we can evaluate the Heaviside function for particular values of x:

=/ x 10?: %- gte [x 10]10

We don't know yet how to store this capability for future use on as-yet-unknown values of x, but we'll see how to do so in a future lesson.

Carefully map how the runes in that statement relate to each other, and notice how the taller structure makes it relatively easier to read and understand what's going on.

Exercise: “Absolute” Value (Around Ten)

Implement a version of the absolute value function, , similar to the Heaviside implementation above. (Translate it to 10 as well since we still can't deal with negative numbers; call this .)

Test it on a few values like 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12.